When you’re nauseous and vomiting, antiemetics can be a lifeline. But not all of them are created equal when it comes to safety. Two big concerns-QT prolongation and drowsiness-can turn a helpful drug into a dangerous one, especially if you’re older, have heart issues, or are taking other meds. Understanding these risks isn’t just for doctors. If you or someone you care about is on these drugs, you need to know what to watch for.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

QT prolongation sounds technical, but it’s simple: it’s when the heart takes too long to recharge between beats. You can see it on an ECG as a longer QT interval. At worst, it can trigger a dangerous rhythm called torsades de pointes, which can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it’s serious.

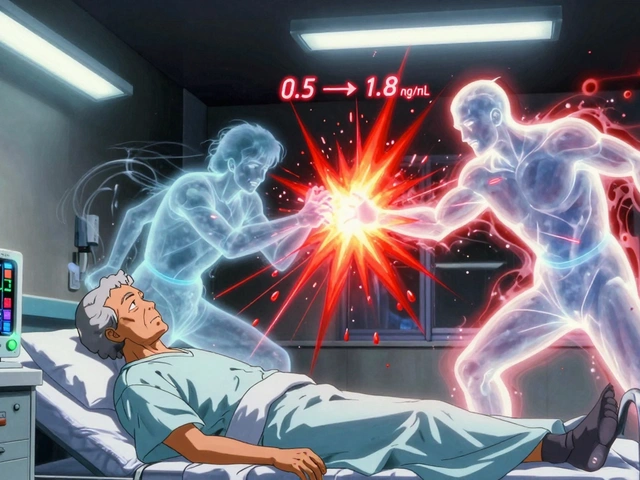

Many antiemetics cause this by blocking a specific potassium channel (IKr) in the heart. That’s the same channel that helps the heart reset after each beat. When it’s blocked, the heart’s electrical cycle slows down. The risk isn’t just about the drug-it’s about the combination. Nearly 91% of cases where QT prolongation led to trouble happened because the patient was also taking other drugs that do the same thing. IV ondansetron, for example, is a common culprit. Studies show that 60% of QT prolongation cases linked to antiemetics involved IV use.

Doctors don’t panic over every small QT change. Clinically significant prolongation means one of three things: a QTc over 500 milliseconds, a rise of more than 25% from your baseline, or a jump of 60 milliseconds or more. But even small changes matter if you’re already at risk-like if you have low potassium, heart disease, or kidney problems.

Which Antiemetics Carry the Highest Risk?

Not all antiemetics are equal. Some are safer than others. Here’s how they stack up.

Ondansetron is one of the most commonly used antiemetics, especially after surgery or during chemotherapy. But it’s also the one with the most documented QT prolongation. At doses over 8 mg IV, it can stretch the QT interval by 17-20 milliseconds. That’s not huge on its own-but in someone with other risk factors, it’s enough to tip the balance. Oral ondansetron doesn’t carry the same risk, which is why many doctors avoid IV unless absolutely necessary.

Granisetron also prolongs QT, but only at high IV doses (over 10 mcg/kg). Interestingly, the transdermal patch version doesn’t affect the QT interval much at all, and it works just as well as the pill. That’s a smart alternative if you need long-term control without heart risk.

Droperidol used to be feared. There was a black box warning for years because of rare cardiac events. But newer studies, including the DORM-1 and DORM-2 trials, show that at antiemetic doses (under 4 mg/day), the risk is extremely low-even lower than once thought. A 2005 study of 85 patients found QT prolongation with droperidol was only about 25 milliseconds on average, and no cases of torsades were reported. The same goes for haloperidol. At the standard 1 mg dose used for nausea, it’s not a real concern. Only cumulative IV doses over 2 mg start to raise flags.

Domperidone is another one that sounds risky. It’s not approved in the U.S., but it’s used elsewhere. Studies in healthy volunteers showed no QT effect even at 80 mg daily. But in older adults or those with liver problems, caution is still advised. It’s not zero risk-just lower than people assume.

Palonosetron stands out. It’s newer, lasts longer (half-life of 40 hours), and doesn’t prolong the QT interval at all. It’s also more effective than ondansetron, especially for delayed nausea after chemo. If you’re at risk for heart rhythm issues, palonosetron is often the best choice.

Olanzapine, originally an antipsychotic, is now used off-label for nausea. It doesn’t affect QT at all, and it causes fewer movement side effects than older drugs. Its downside? It’s not as well studied for nausea as other options, and it can cause drowsiness.

Drowsiness: The Other Hidden Risk

QT prolongation gets all the attention, but drowsiness can be just as disruptive-or dangerous. If you’re driving, operating machinery, or caring for kids, being sleepy isn’t just inconvenient. It’s risky.

Promethazine is one of the most sedating antiemetics out there. It’s often used for motion sickness and nausea, but it knocks people out. Even small doses can cause deep sleepiness, especially in older adults.

Prochlorperazine is less sedating than promethazine, but still causes drowsiness in many. It’s often used in emergency rooms, and patients often report feeling foggy afterward.

Metoclopramide crosses into the brain and blocks dopamine there. That’s why it can cause muscle spasms, tremors, and restlessness-not just nausea relief. It also causes drowsiness and QT prolongation, so it’s a double-risk drug.

On the flip side, palonosetron and ondansetron are much less sedating. You’re unlikely to feel sleepy after taking them. That’s why they’re preferred for patients who need to stay alert.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone needs to avoid these drugs. But some people should be extra careful:

- People over 65-older hearts are more sensitive to drug effects

- Those with heart disease, especially prior arrhythmias

- People with low potassium or magnesium (common after vomiting or diuretics)

- Those on multiple QT-prolonging drugs (antibiotics, antidepressants, antifungals)

- Patients with kidney or liver failure-drugs build up in the body

- People taking high doses or IV forms of ondansetron or granisetron

If you’re healthy, young, and have no heart issues or electrolyte problems, the risk from most antiemetics is very low. One study even says that in these patients, “clinically relevant ECG changes have not been reported.” But if you’re in any of the high-risk groups, don’t assume it’s safe. Ask your doctor to check your ECG before starting, or choose a safer option.

What to Do Instead

You don’t have to suffer through nausea. There are safer alternatives:

- Palonosetron for chemo or post-op nausea-no QT risk, longer-lasting, more effective

- Olanzapine for severe nausea, especially if drowsiness isn’t a problem

- Dimenhydrinate or meclizine for motion sickness-minimal QT effect

- Benzodiazepines like lorazepam-used in palliative care for nausea and anxiety, no QT prolongation

- Transdermal granisetron-same effect as oral, less heart impact

And remember: oral forms are almost always safer than IV. If you’re not in the hospital, ask if you can take a pill instead of getting an injection.

When to Call for Help

Most people take antiemetics without issue. But if you feel:

- Your heart racing or skipping beats

- Dizzy or fainting, especially after taking the drug

- Unusual fatigue or confusion

-get medical help right away. These could be early signs of a dangerous rhythm. Don’t wait. Bring your medication list with you.

The bottom line? Antiemetics save lives. But they’re not harmless. The key is matching the drug to the person-not just the symptoms. If you have heart concerns, ask about palonosetron or olanzapine. If drowsiness is a problem, skip promethazine. And never take more than prescribed. A little caution goes a long way.

15 Comments

Jacob Hepworth-wain

Nov 29 2025I've seen this play out in the ER a dozen times. IV ondansetron gets handed out like candy, but the QT risks are real. One elderly patient coded after three doses. We switched to oral and never looked back. Just say no to unnecessary IVs.

Geethu E

Dec 1 2025As a nurse in Mumbai, I've seen promethazine knock out entire families. Grandmas sleeping for hours after one pill. We stopped using it for motion sickness years ago. Meclizine or ginger tea works better and doesn't turn people into zombies.

Craig Hartel

Dec 2 2025Love this breakdown. Palonosetron is my go-to for chemo patients now. No drowsiness, no QT drama. It's pricier but worth every penny when your grandma can actually watch TV after treatment instead of napping for 12 hours.

Bruce Hennen

Dec 4 2025The author incorrectly states that droperidol has a 'black box warning.' That warning was lifted in 2013 after rigorous meta-analyses showed no significant risk at antiemetic doses. This misinformation undermines the credibility of the entire piece.

Jake Ruhl

Dec 5 2025They're hiding the truth. Big Pharma doesn't want you to know that all these drugs are just chemical mind control. QT prolongation? That's just the body screaming because the system is rigged. They want you dependent. Palonosetron? It's a placebo with a patent. The real cure is fasting and prayer. I've healed myself with lemon water and willpower.

Chuckie Parker

Dec 5 2025America's healthcare system is broken. We're giving IV drugs to old people like they're candy. In my day, we just drank ginger tea and toughed it out. Now we got a pill for everything and people can't even stand up without a doctor's note.

Michael Segbawu

Dec 5 2025This is why I don't trust doctors anymore. They don't care about you. They just want to push the expensive stuff. Ondansetron? That's a cash cow. Palonosetron? Same thing. They're all the same. Just give me a banana and some rest. That's what worked in 1987.

Leah Doyle

Dec 6 2025My mom took ondansetron after chemo and felt fine... until she passed out at the grocery store. Turned out her potassium was low and the drug pushed her over the edge. We switched to olanzapine and she's been back to gardening. So glad we found a safer option! ❤️

Chris Kahanic

Dec 6 2025The data on transdermal granisetron is compelling. We've used it in our palliative care unit for six months now. No QT changes, no sedation, and patients report better compliance than with oral tablets. It's a quiet revolution in nausea management.

Alexis Mendoza

Dec 8 2025It's funny how we treat nausea like an emergency when it's often just the body saying 'slow down.' We rush to medicate instead of asking why the person is nauseous in the first place. Maybe it's anxiety. Maybe it's dehydration. Maybe it's just needing to lie down. Medicine should heal, not just suppress.

Michelle N Allen

Dec 8 2025I read this whole thing and still don't know what to do. The article says one thing then contradicts it later. Ondansetron bad but okay if oral. Droperidol risky but not really. Palonosetron good but expensive. Just tell me which one to pick already.

Madison Malone

Dec 8 2025This is so helpful. My dad had a heart episode after getting IV ondansetron and we didn't even know it could do that. Now I print this out and bring it to every appointment. Doctors don't always know the risks unless you ask. Thank you for making this clear.

Aarti Ray

Dec 10 2025In India we use domperidone all the time. No one even thinks about QT. But my uncle with liver issues got dizzy after two days. So we stopped. Maybe it's not safe for everyone. Good to know the details.

Alexander Rolsen

Dec 11 2025You people are so naive. This isn't about medicine. It's about control. The FDA, Big Pharma, and the AMA are all in bed together. They don't care if you live or die. They care about profits. QT prolongation is a distraction. They want you afraid so you'll keep taking their pills. Wake up.

Kim Clapper

Dec 12 2025This article is dangerously oversimplified. You mention 'clinically significant' QT prolongation thresholds, yet ignore the fact that many patients have baseline ECG abnormalities that aren't accounted for. You also fail to mention that polymorphisms in the hERG gene can make someone 10x more susceptible. This is not patient education-it's patient endangerment.