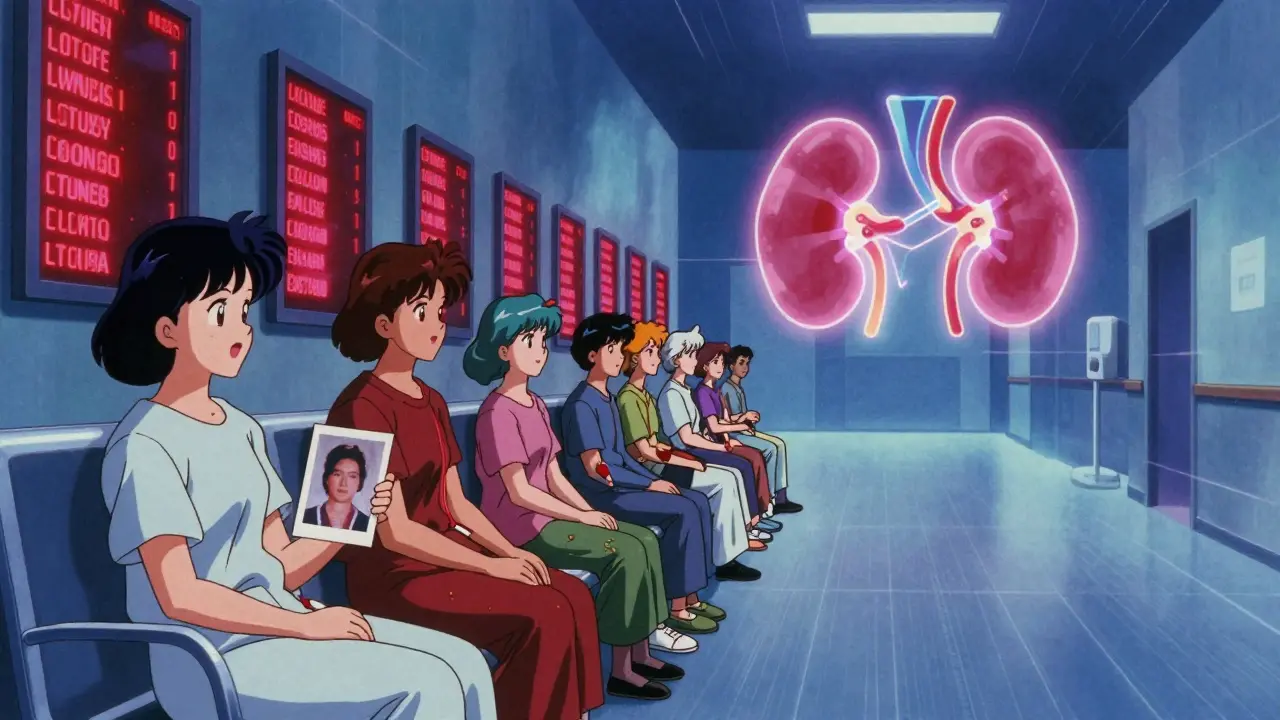

Getting listed for a kidney transplant isn’t something that happens overnight. It’s a long, detailed process that starts long before you even see the operating room. If you’re waiting for a new kidney-whether from a deceased donor or a living one-you need to understand what comes before the surgery. The evaluation, the waitlist, and finding a living donor are three separate but deeply connected parts of the journey. And getting through them successfully can make all the difference in how long you wait and how well you recover.

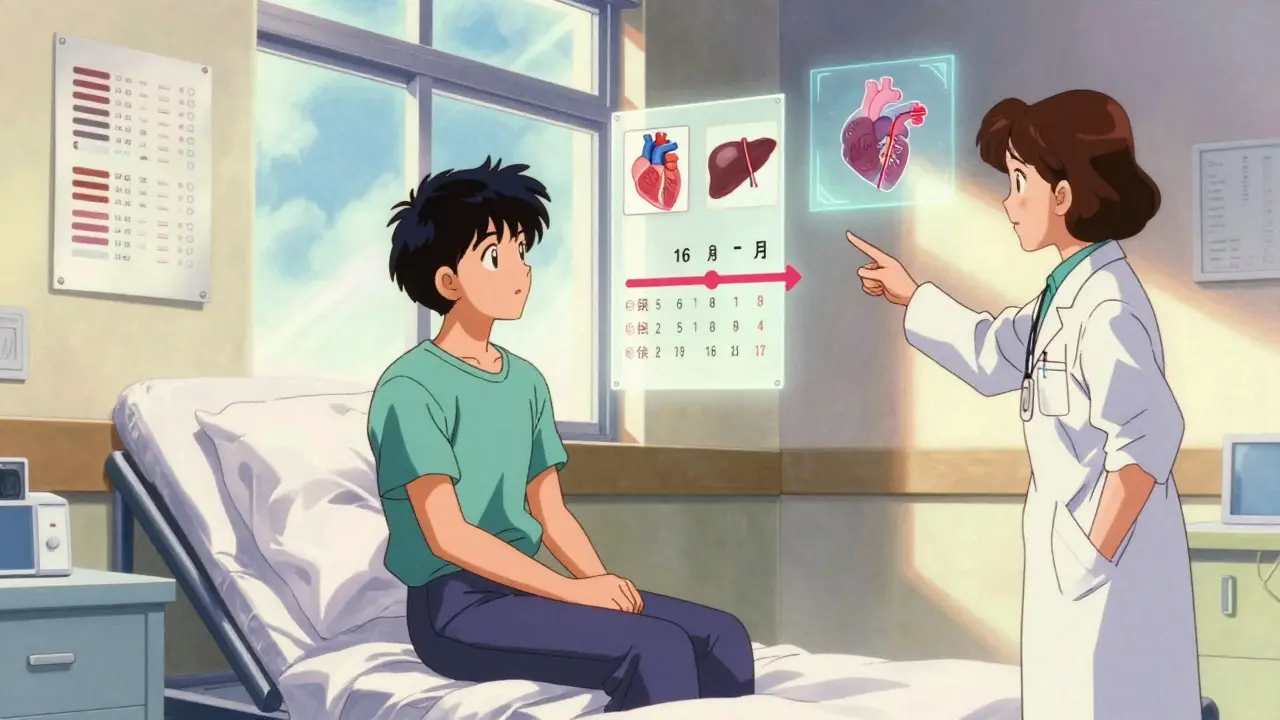

What Happens During the Transplant Evaluation?

The evaluation is your first real step toward a transplant. It’s not just a checkup. It’s a full medical and personal audit to make sure you’re physically and emotionally ready for the procedure and the lifelong care that follows. Every transplant center in the U.S. follows strict national guidelines set by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and most require you to complete this process within 12 weeks of your first appointment. You’ll start with a referral from your nephrologist, usually when your kidney function drops below an eGFR of 20. From there, you’ll be assigned a transplant coordinator who becomes your main point of contact. They’ll schedule everything: blood tests, imaging, specialist visits. You’ll need to bring your complete medical history-ideally, five years of records, including dialysis logs if you’ve had them. Missing appointments is one of the biggest reasons evaluations get delayed. About 18% of candidates fall behind simply because they miss a test or a meeting. Medically, you’ll go through a long list of tests. Blood type and tissue matching (HLA typing) are basic. You’ll be screened for HIV, hepatitis B and C, and other infections using the latest CDC-recommended tests. Your heart gets checked too: an echocardiogram to measure how well your heart pumps, a stress test to see if you can handle physical exertion (you need to hit at least 5 metabolic equivalents), and an EKG. Liver and kidney function tests, including albumin and platelet counts, must be in normal range. For men over 50, a PSA test is required. Women need regular mammograms and Pap smears. But the medical side is only half the story. You’ll also meet with a transplant social worker and a psychologist. They’ll ask hard questions: Who will help you after surgery? Can you get to your follow-up appointments? Do you have money saved for medications? Northwestern Medicine, for example, requires proof you have at least $3,500 in liquid assets to cover your first year of anti-rejection drugs. They’re not trying to be harsh-they’re trying to prevent you from stopping your meds later because you can’t afford them. That’s the #1 reason transplants fail after the first year. The whole process takes 15 to 25 appointments and usually 8 to 16 weeks. High-volume centers finish faster-sometimes 23% quicker-because they’ve streamlined scheduling. If you’re lucky, your coordinator might group your tests so you don’t have to come in 10 separate times. One patient on Reddit said their coordinator turned 12 weeks of visits into six by coordinating everything in blocks. That kind of support matters.How Do You Get on the Waitlist?

Once all your tests are done, your case goes to the transplant selection committee. This group includes a surgeon, nephrologist, social worker, psychiatrist, and coordinator. They meet weekly. Their job isn’t just to approve you-they’re also there to protect you. If they see you’re not ready, they’ll tell you why and what you need to fix before reapplying. The committee looks at three things: medical suitability, psychosocial readiness, and fairness. Medical reasons for denial include active cancer, uncontrolled infection, severe heart disease, or a BMI over 40. But surprisingly, psychosocial issues cause more failures than medical ones. About 32% of candidates are turned down because of concerns about support systems, substance use, or inability to follow complex medication schedules. That’s more than heart problems or obesity. Insurance is another major hurdle. Medicare covers 80% of transplant costs, but you still need to pay your deductible-averaging $4,550 a year. Private insurance usually covers 70-90%, but many plans require pre-authorization for every test. One in four Medicaid patients face delays because their insurance denies coverage for a specific test. That can add weeks, even months, to your timeline. The National Kidney Foundation says 28.7% of all evaluation delays come from insurance issues. If you’re approved, you’re officially listed. But being on the list doesn’t mean you’ll get a kidney soon. As of January 2024, over 102,000 people in the U.S. were waiting for a kidney. The average wait time? 3.6 years. And it’s not first-come, first-served. Your wait time depends on your blood type, tissue match, and how sensitized your immune system is. People with high levels of antibodies (cPRA over 98%) get priority because finding a match is so hard.What Is a Living Donor, and How Does It Work?

The best way to shorten your wait? A living donor. About 39% of all kidney transplants in 2023 came from living donors-mostly family members, friends, or even strangers. The reason? Kidneys are the only organ you can live without one of. And living donor transplants have higher success rates: 96.3% of these kidneys still work after one year, compared to 94.1% for deceased donor kidneys. Finding a living donor isn’t just about asking someone. The donor has to go through their own evaluation. They need to be healthy, free of diabetes or high blood pressure, and have normal kidney function. Their blood type must match yours-or be compatible. Even if they’re not a direct match, they might still help through the Kidney Paired Donation Program. This program swaps donors between pairs. For example, if your sister wants to donate but her blood type doesn’t match yours, she can donate to someone else whose donor matches you. In 2023, this program helped 1,872 people get transplants. The donor evaluation is faster now. Leading centers use “rapid crossmatch” protocols that cut the process from 6-8 weeks down to just 2-3. Donors still need blood tests, imaging, psychological screening, and a full physical. But they’re not evaluated for “worthiness.” They’re evaluated for safety. If they’re healthy enough to donate, they’re eligible. Many donors worry about costs. But by law, the recipient’s insurance covers all donor-related medical expenses. Some organizations also help with travel and lost wages. Still, the emotional weight can be heavy. One donor told me, “I didn’t realize how much guilt I’d feel if something went wrong.” That’s why counseling is mandatory for donors too.

What Happens If You Don’t Get Approved?

Not everyone makes it to the waitlist. About 12% of evaluations are canceled because testing isn’t completed. Others are denied for medical or psychosocial reasons. But denial isn’t the end. Many people get re-evaluated after fixing the issue-losing weight, quitting smoking, getting mental health support. If you’re denied because of financial concerns, don’t give up. Talk to your transplant center’s financial counselor. There are programs that help with medication costs, transportation, and even housing near the hospital. The American Kidney Fund and National Transplant Foundation offer grants and support networks. If you’re denied for mental health reasons, work with a therapist. Many centers will re-evaluate you after six months of consistent care. The goal isn’t to turn you away-it’s to make sure you’re set up to succeed.What Can You Do to Speed Things Up?

There are things you can control. First, stay organized. Keep a notebook or digital folder with all your test results, appointment dates, and insurance communications. Use your patient portal. Check it daily. If a test is missing, call your coordinator right away. Second, bring a support person to every appointment. Not just for moral support. They’ll remember things you miss. They can ask questions you didn’t think of. And if you’re feeling overwhelmed, they can speak up. Third, start talking to your family and friends about donation. Don’t wait until you’re desperate. Say, “I’m going to be evaluated for a transplant. If you’re healthy and willing, I’d like to know if you’d consider being tested.” Most people don’t think they’re qualified. They’re often surprised to find out they are. And finally, don’t delay. Research shows that people who finish evaluation within 90 days of their first referral have an 11.3% higher chance of surviving five years after transplant. The sooner you start, the sooner you can move forward.

What’s New in Kidney Transplantation?

The field is changing fast. In 2023, over 200 HIV-positive patients received kidneys from other HIV-positive donors-something that was impossible just a decade ago. The HOPE Act opened the door. Now, people with well-controlled HIV can be both donors and recipients. New allocation rules now give priority to patients with the highest antibody levels, making it easier for those who’ve had previous transplants or pregnancies to find matches. And by 2026, new federal rules are expected to reduce the number of people who abandon their evaluation because they can’t afford it. But challenges remain. Black patients still wait longer than White patients-even after adjusting for medical need. Centers that use standardized evaluation pathways have cut that gap in half. If your center doesn’t have one, ask if they’re planning to implement one. Equity matters.Final Thoughts

Preparing for a kidney transplant is exhausting. It’s expensive. It’s emotional. But it’s also the most effective treatment for end-stage kidney disease. Every step-every blood draw, every appointment, every conversation about money and mental health-is part of building a future where you’re not tied to a machine, where you can sleep through the night, where you can walk without being out of breath. You’re not just waiting for a kidney. You’re preparing for a second chance. And the more you understand the process, the more power you have to move through it.How long does the kidney transplant evaluation take?

The evaluation typically takes 8 to 16 weeks, depending on your health, how quickly you complete tests, and your insurance approval timeline. Living donor candidates often finish faster-around 8 to 12 weeks-because the donor’s evaluation can run in parallel. High-volume transplant centers complete evaluations up to 23% faster than smaller ones due to better coordination.

Can I be listed for a transplant if I have diabetes?

Yes, but your diabetes must be well-controlled. Uncontrolled blood sugar increases the risk of infection and poor wound healing after transplant. Most centers require an HbA1c below 8% and no history of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic complications like advanced nerve or eye damage. Some centers may require you to lose weight or stabilize your glucose levels before listing.

Do I need to be off dialysis to get on the waitlist?

No. In fact, most people are listed while still on dialysis. Waiting until you’re off dialysis can be dangerous-your health may decline too much to qualify for transplant. Being on dialysis doesn’t disqualify you. What matters is your overall health, heart function, and ability to handle surgery and lifelong medications.

What if I can’t afford transplant medications?

Anti-rejection drugs cost about $32,000 per year. Medicare covers 80% for three years after transplant, then you may need supplemental insurance. Many states have medication assistance programs, and nonprofit organizations like the American Kidney Fund and Patient Access Network Foundation offer grants. Transplant centers have financial counselors who help you apply for these programs before you’re listed.

Can someone who is overweight be a living donor?

Yes, but donors with a BMI over 30 are evaluated more carefully. Obesity increases surgical risk and can affect long-term kidney health. Most centers require donors to lose weight before donation if their BMI is above 35. Some centers allow donation at BMI 30-35 if the donor is otherwise healthy and commits to weight loss after donation. Each case is reviewed individually.

What happens if my living donor backs out?

If your living donor decides not to proceed, you go back on the deceased donor waitlist. Your position doesn’t reset-you keep your original wait time. The transplant team will support you emotionally and help you explore other options, including paired donation programs or continuing to wait for a deceased donor kidney. It’s common for donors to change their minds, and centers are prepared to handle this.

How do I know if I’m a good candidate for a living donor transplant?

You’re a strong candidate if you’re in good overall health, have no active infections or cancer, and can follow a strict medication schedule. Having a willing, healthy donor who passes medical and psychological screening is the key. Living donor transplants offer better outcomes and shorter wait times, so if you have someone in mind-even a friend or coworker-it’s worth starting the conversation early.

Next steps: Talk to your nephrologist about getting referred to a transplant center. Ask for a list of nearby centers and their average evaluation times. Start gathering your medical records. And don’t be afraid to ask your circle: “Would you consider being tested as a living donor?” The right person might be closer than you think.

14 Comments

Jasmine Yule

Dec 31 2025Just read this and cried. Not because I’m waiting, but because my mom did this 5 years ago and I watched her go through EVERYTHING they mentioned. The paperwork, the insurance battles, the sleepless nights worrying about meds. She got her kidney from a stranger. A stranger who didn’t even tell her name until after the surgery. 🤍

Greg Quinn

Dec 31 2025It’s wild how the system treats kidneys like a lottery ticket when they’re literally the only organ you can donate and still live. We let people die waiting while we debate ethics and insurance tiers. Meanwhile, the science is ready-we just ain’t ready to care enough.

Also, why is it that the people who need this most are the ones with the least access to paperwork, transport, and time? The system’s rigged, but at least now they’re trying to fix the equity gap. Small wins.

Lisa Dore

Dec 31 2025You’re not alone. Seriously. If you’re reading this and you’re in the middle of eval, take a breath. You’re doing better than you think. I was denied twice before I got through-first because I was ‘too anxious,’ then because my insurance messed up the HbA1c report. Took me 11 months, but I’m on the list now. And yes, I still cry in the shower sometimes. That’s okay.

Also-ask your cousin. Or your coworker. Or your neighbor. You’d be shocked who says yes.

Duncan Careless

Jan 2 2026got my eval done last year. 14 appts, 3 missed bc of work, got flagged. had to redo 2 tests. took 6 months. insurance denied the cardiac stress test 3 times. finally got it after my doc called them directly. still waiting. 3.5 years in. hope the next one’s mine.

ps: my sister’s getting tested. she’s scared. so am i.

Sharleen Luciano

Jan 3 2026Let’s be honest-most of these patients aren’t ‘ready.’ They’re just desperate. The psych evals exist for a reason: people who can’t manage their own meds shouldn’t get a kidney. You don’t get a liver transplant if you’re still drinking. Why should kidneys be different?

And don’t get me started on the ‘living donor’ guilt-trip culture. No one owes you an organ. Stop romanticizing altruism. It’s not noble-it’s a high-risk surgery with zero benefit to the donor.

Also, why are we still using 1990s insurance protocols in 2024? Pathetic.

Louis Paré

Jan 3 2026Oh wow, so now we’re giving priority to people with high antibodies? Because they’re ‘hard to match’? That’s just medical elitism dressed up as fairness. What about the guy who’s been waiting 8 years because he’s Black and the system ignores him? You’re optimizing for logistics, not justice.

And ‘rapid crossmatch’? Sounds like corporate efficiency porn. They’re rushing donors through because they want more transplants on their quarterly report. Not because they care about the person.

Also, why is everyone so quiet about the fact that 39% of transplants come from living donors? That’s not progress-that’s exploitation waiting to be regulated.

Marie-Pierre Gonzalez

Jan 4 2026Thank you for writing this with such care. 🙏 I am a nurse in Toronto, and I see this every week. The emotional toll on families is invisible to most. One mother donated her kidney to her son-and then developed hypertension six months later. No one warned her. No one followed up. The system forgets the donors.

Also, I’ve seen patients cry because they can’t afford the $32K/year meds. And then they’re told to ‘apply for grants.’ Like that’s a solution. It’s not. It’s a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound.

Aliza Efraimov

Jan 6 2026THIS. This is the most comprehensive thing I’ve ever read on transplant prep. I’m a nephrology nurse and I still learned three new things. The part about the $3,500 liquid asset requirement? That’s REAL. I had a patient who had to sell her wedding ring to qualify. She didn’t even tell her husband.

Also-don’t underestimate the power of bringing someone to your appts. My patient brought her 14-year-old daughter. The girl asked the social worker, ‘Why does he have to prove he’s good enough to live?’ And the whole room just… stopped. That’s the moment you realize this isn’t medicine. It’s a test of worthiness.

Fabian Riewe

Jan 8 2026My uncle got a kidney from a guy he met at the gym. They didn’t even know each other well. Just chatted about protein shakes. Then the guy said, ‘Hey, I’m O-negative, you’re A-positive, I think I’m a match.’ Turned out he was. Surgery was in 8 weeks. Now they text every Sunday. That’s wild.

Also-yes, you can be overweight and donate. My cousin was BMI 33 and they let her do it. She lost 20 lbs after. She says it was the best thing she ever did. Even if she didn’t ‘save’ my uncle, she changed his life. That’s enough.

Manan Pandya

Jan 8 2026As someone from India, I find it fascinating how the US system is so structured yet so broken. In my country, many transplants happen in private hospitals with little oversight. But the donor evaluation here? It’s almost too thorough. I worry it’s more about liability than care.

Still, the paired donation program is genius. We don’t have that here. Maybe we should. Also-why isn’t this information on every nephrology clinic’s website? It should be mandatory reading.

Henriette Barrows

Jan 9 2026My sister got her kidney last year. She’s back to hiking. She sleeps through the night. She doesn’t need to be near a bathroom every 20 minutes. I cried when I saw her eat pizza without checking her sodium intake first.

But the real hero? My mom. She got tested. Didn’t match. Then she found out her blood type could help someone else-and she donated to a stranger. Two weeks later, my sister got the call.

It’s not magic. It’s just people showing up.

Jim Rice

Jan 11 2026Wait, so if you’re poor, you get denied? And if you’re rich, you get a kidney in 6 months? That’s not medicine, that’s capitalism. And don’t give me that ‘financial counselor’ BS. They’re just gatekeepers with clipboards.

Also, why is the ‘living donor’ narrative always so uplifting? What about the 12% of donors who develop chronic pain? Or the ones who regret it? No one talks about that. It’s all ‘hero’ and ‘miracle’-until they’re not.

Nisha Marwaha

Jan 13 2026From a clinical perspective, the OPTN’s recent shift toward cPRA prioritization represents a paradigmatic evolution in organ allocation logic, transitioning from time-based to immunological risk stratification. This aligns with emerging literature on alloimmunization burden and graft survival trajectories. However, structural inequities in access to pre-transplant immunosuppressive optimization remain unaddressed, particularly in Medicaid populations with limited access to HLA crossmatch refinement.

Additionally, the rapid crossmatch protocol, while logistically efficient, may inadvertently compromise donor safety by compressing longitudinal psychosocial assessment windows-a potential violation of the Belmont principle of beneficence.

Fabian Riewe

Jan 15 2026That’s why you bring someone with you. My buddy came to my last appt. He asked the coordinator, ‘So what happens if she gets a kidney and can’t pay for the meds?’ And the coordinator said, ‘Then we get her into a grant program.’

That’s the moment I realized-this system isn’t designed to fail. It’s just really, really bad at helping people who don’t know how to ask.