Melanoma Treatment Decision Helper

Select Patient Characteristics

Recommended Treatment Plan

Select patient characteristics and click "Determine Treatment Approach" to see recommendations.

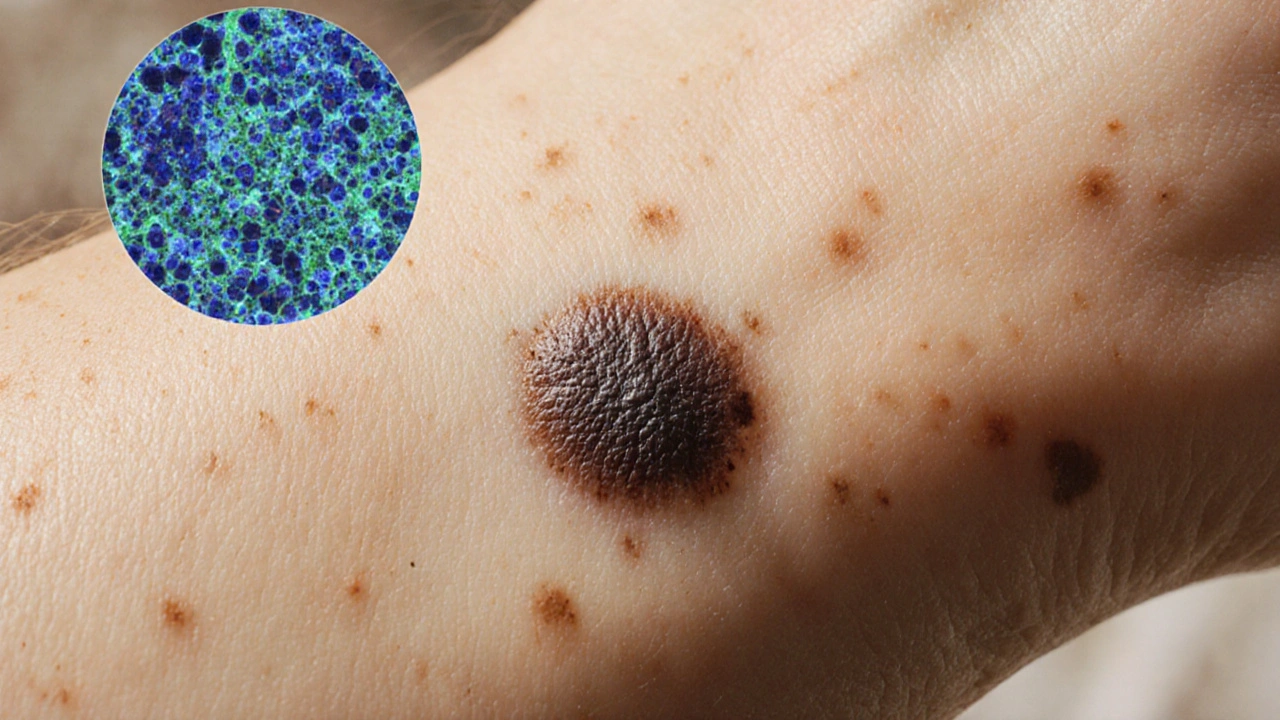

Melanoma is a malignant tumor originating from pigment‑producing melanocytes, most often found on skin but also possible in the eye and mucous membranes. It accounts for about 1% of skin cancers yet causes the majority of skin‑cancer deaths because of its tendency to metastasize early. Traditional chemotherapy offers limited benefit, pushing researchers toward targeted therapy-drugs that zero in on molecular abnormalities driving each tumor.

Key Takeaways

- Targeted therapy blocks specific mutations such as BRAF, KIT, or NRAS that fuel melanoma growth.

- FDA‑approved BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) and MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib) improve survival when combined.

- Choosing targeted drugs depends on genetic testing, disease stage, and patient health.

- Side‑effects differ from immunotherapy; monitoring includes liver tests, skin exams, and cardiac checks.

- Ongoing trials explore next‑gen inhibitors, combination regimens, and resistance‑busting strategies.

What Is Melanoma?

A diagnosis of melanoma triggers a cascade of decisions. Staging follows the TNM system (tumor size, nodal involvement, metastasis). Early‑stage disease (I‑II) is usually treated with surgery alone, while stage III and IV often require systemic therapy.

Key prognostic factors include ulceration, mitotic rate, and genetic profile. The latter has become the cornerstone for modern treatment selection, especially as precision oncology tools mature.

Understanding Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy refers to agents that bind to a specific protein or signaling pathway altered in cancer cells. Unlike chemotherapy, which attacks any rapidly dividing cell, these drugs aim to spare normal tissue, reducing collateral damage.

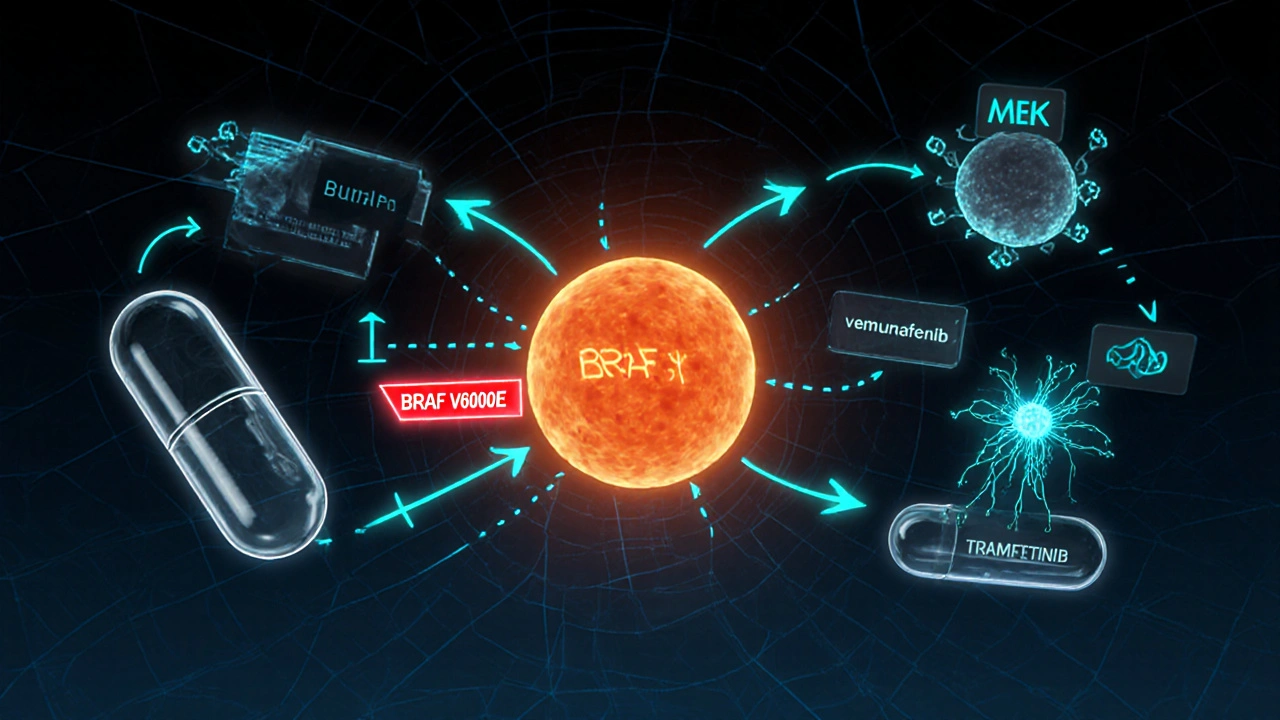

In melanoma, the most actionable targets are oncogenic mutations that keep the MAPK (mitogen‑activated protein kinase) pathway permanently switched on. Interrupting this signal can halt tumor growth and sometimes shrink existing lesions.

Common Genetic Targets in Melanoma

BRAF mutation is the single most frequent driver, present in about 40‑50% of cutaneous melanomas. The V600E and V600K variants account for the majority, producing a constitutively active BRAF kinase.

MEK inhibitor targets the downstream kinase MEK1/2, which transmits the BRAF signal to the nucleus. Blocking MEK amplifies the effect of BRAF inhibition and delays resistance.

Less common but still clinically relevant alterations include:

- NRAS mutation found in roughly 15‑20% of cases, activating the same MAPK cascade upstream of BRAF.

- KIT mutation seen in acral, mucosal, and chronically sun‑damaged melanomas, driving the receptor tyrosine kinase pathway.

Approved Targeted Drugs and How They Work

Four agents have secured FDA approval for BRAF‑mutant melanoma, all used in combination with a MEK inhibitor to improve outcomes and limit skin toxicities.

| Drug | Target | Approved Indication | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vemurafenib | BRAF V600E/K | Metastatic BRAF‑mutant melanoma | Photosensitivity, arthralgia, rash |

| Dabrafenib | BRAF V600E/K | Metastatic BRAF‑mutant melanoma | Fever, fatigue, hyperkeratosis |

| Trametinib | MEK1/2 | Combined with dabrafenib | Diarrhea, edema, rash |

| Cobimetinib | MEK1/2 | Combined with vemurafenib | Serum creatinine rise, photosensitivity |

For KIT‑mutant melanoma, the multikinase inhibitor imatinib is sometimes used off‑label, though response rates hover around 20%.

NRAS‑mutant disease lacks a direct inhibitor; treatment usually leans on immunotherapy or attempts at downstream MEK inhibition, which has modest efficacy.

When to Use Targeted Therapy vs Immunotherapy

Modern melanoma care often pairs Immunotherapy-especially PD‑1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab or nivolumab-with or after targeted agents. The decision hinges on three practical questions:

- Is a targetable mutation present? If yes, start BRAF/MEK blockade for rapid disease control.

- How aggressive is the disease? Fast‑growing visceral metastases often need the quick tumoricidal effect of targeted therapy.

- What is the patient’s overall health? Those with autoimmune conditions may tolerate targeted drugs better than checkpoint inhibitors.

Evidence from the COMBI‑Ad trial shows that patients who begin with BRAF/MEK inhibitors and later switch to PD‑1 blockade achieve comparable overall survival to those starting with immunotherapy, but the sequence can affect quality‑of‑life metrics.

Managing Side Effects and Monitoring

Every targeted agent carries a unique safety profile. A practical monitoring plan includes:

- Baseline ECG and echocardiogram for QT‑prolongation risk (especially with vemurafenib).

- Monthly liver function tests; elevations may signal hepatotoxicity.

- Dermatology check‑ups every 6-8 weeks to catch early skin lesions, including secondary squamous cell carcinoma.

- Patient education on photosensitivity: sunscreen SPF30+, protective clothing, and avoidance of peak sun hours.

If grade3-4 toxicities appear, pause the drug, treat symptomatically, and consider dose reduction or switching to the alternative BRAF/MEK pair.

Future Directions and Clinical Trials

Resistance remains the biggest hurdle; most patients develop progression after 12‑18 months on BRAF/MEK combos. Researchers are pursuing three main strategies:

- Next‑generation inhibitors that bind to alternative sites on BRAF, overcoming the classic “gatekeeper” resistance.

- Triplet combos adding a checkpoint inhibitor to BRAF/MEK therapy from day1, aiming for deeper, durable responses.

- Biomarker‑driven trials that match patients to emerging agents based on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) profiles.

As of 2025, the phaseIII TRICOT trial reported a 24‑month overall survival of 68% for the triplet regimen versus 55% for the doublet, sparking optimism for a new standard of care.

Frequently Asked Questions

What genetic test is needed before starting targeted therapy?

A comprehensive melanoma panel (often a next‑generation sequencing assay) checks for BRAF, NRAS, and KIT mutations. The test can be performed on the primary tumor or a metastatic biopsy, and results typically return within 10‑14 days.

Can I combine targeted therapy with immunotherapy?

Yes, but timing matters. Current guidelines suggest starting with BRAF/MEK inhibitors for rapid control, then transitioning to a PD‑1 blocker once the disease stabilizes. Simultaneous use increases toxicity and is usually reserved for clinical trials.

What are the most common side effects I should expect?

Skin reactions (rash, photosensitivity), fever, joint pain, and elevated liver enzymes are typical. Severe complications like heart rhythm changes or secondary skin cancers are rarer but require prompt medical attention.

How long will I stay on a targeted drug?

Treatment continues until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. On average, patients remain on therapy for 12‑18 months, after which a switch to immunotherapy or a clinical‑trial agent is considered.

Are targeted therapies covered by health insurance in New Zealand?

Yes, the government‑funded PHARMAC program lists vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and the MEK inhibitors for eligible patients with confirmed BRAF mutations. Prior authorization and genetic testing are required.

11 Comments

Joery van Druten

Oct 3 2025Targeted therapy has indeed reshaped melanoma management. Testing for BRAF, NRAS, or KIT mutations before starting treatment is essential to choose the right regimen.

Melissa Luisman

Oct 5 2025Honestly, the post glosses over the fact that many patients never get timely genetic testing, which defeats the whole purpose of targeted therapy.

Alice Witland

Oct 6 2025Oh great, another fancy table of drugs – because we all needed more bullet points to feel educated.

Chris Wiseman

Oct 8 2025Indeed, the evolution of melanoma treatment mirrors the grand narrative of modern medicine, where the relentless pursuit of precision intersects with the humble realities of patient care; one might say it is a tale of paradox and promise, of hope gilded by the starkness of biological complexity, and, as such, it warrants a contemplative pause to truly grasp its magnitude. The inception of BRAF inhibitors heralded a turning point, offering a beacon of rapid disease control for those burdened with V600 mutations, yet this beacon is not without its shadows. Resistance inevitably surfaces, often after a year or so, compelling clinicians to grapple with the inexorable march of tumor adaptation. Consequently, the addition of MEK inhibitors emerged not merely as a convenience, but as a strategic countermeasure, designed to forestall reactivation of the MAPK cascade. Yet, even this duo does not guarantee permanence; secondary skin cancers and hepatic toxicity loom as ever‑present specters. One must also consider the socioeconomic contours that shape access, for in many regions the cost of combination therapy remains prohibitive, relegating patients to suboptimal alternatives. Moreover, the interplay between targeted agents and immunotherapies invites both optimism and caution, as concurrent administration can amplify adverse events, while sequential strategies strive to balance efficacy and tolerability. In the grand mosaic of therapeutic options, patient selection remains paramount, guided by genomic profiling, disease burden, and comorbidities. While the literature celebrates unprecedented survival curves, it simultaneously reminds us that every statistical gain translates to a human story, fraught with side‑effects, monitoring burdens, and emotional tolls. As we look forward, the horizon glimmers with next‑generation inhibitors seeking to outmaneuver resistance mechanisms, and triplet regimens that promise deeper, more durable responses. Yet, the path forward must be navigated with rigor, humility, and an unwavering commitment to the individual behind the data.

alan garcia petra

Oct 9 2025Stay positive! Even if side effects pop up, they’re usually manageable, and you’ll still have options down the road.

Allan Jovero

Oct 11 2025It is imperative to underscore that any initiation of BRAF/MEK inhibition must be accompanied by baseline cardiac and hepatic assessments, as mandated by current clinical guidelines.

Andy V

Oct 12 2025While the guidance above is technically correct, many clinicians overlook these checks, leading to preventable complications.

Tammie Sinnott

Oct 14 2025Fun fact: the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib actually cuts the risk of secondary skin cancers by about 30% compared to BRAF inhibitor monotherapy.

Michelle Wigdorovitz

Oct 15 2025That statistic really highlights why the double‑hit approach is the current gold standard, especially for patients with aggressive disease trajectories.

Arianne Gatchalian

Oct 17 2025I understand how overwhelming all these options can feel; remember that your care team is there to tailor the plan to your unique situation.

Aly Neumeister

Oct 18 2025Absolutely - you’ll want to keep an eye on liver enzymes, skin changes, and heart rhythm; it’s all part of the process.