Imagine trying to button a shirt, lift a grocery bag, or simply walk across a room, and each movement feels shaky, uncoordinated, or downright impossible. That’s the reality for many people living with poor muscle control. In this article we’ll break down what muscle control actually means, why it can go wrong, and how those hiccups spill over into the things we do every day.

What is Muscle Control?

Muscle control is the ability of the nervous system to coordinate muscle activation so that movements are smooth, precise, and purposeful. It relies on three key components: strength (how much force a muscle can generate), timing (when muscles fire), and proprioception (the sense of body position). When these pieces work together, you can swing a tennis racket or type on a keyboard without thinking. When they don’t, actions become clumsy, fatigued, or unsafe.

Common Causes of Poor Muscle Control

People often assume muscle weakness is only caused by a lack of exercise, but the picture is broader. Below are the most frequent culprits:

- Neurological disorders such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or cerebral palsy disrupt the brain‑spinal cord pathways that send signals to muscles.

- Peripheral nerve injuries from trauma or compression (e.g., carpal tunnel) impair signal transmission to specific muscle groups.

- Musculoskeletal conditions like severe osteoarthritis or chronic low‑back pain alter joint mechanics, forcing muscles to overcompensate.

- Aging naturally reduces motor unit recruitment speed and proprioceptive feedback, leading to slower, less coordinated movements.

- Medication side effects (e.g., sedatives, certain antihypertensives) can dull the central nervous system’s command over muscles.

Daily Activities That Can Suffer

When muscle control falters, the impact ripples through almost every Activity of Daily Living (ADL) - the basic tasks we need to survive and thrive. Here are the most common pain points:

- Personal hygiene: Brushing teeth, shaving, or washing hair requires fine motor control of the arms and hands.

- Eating and drinking: Cutting food, using utensils, or managing a cup demands coordinated hand‑eye movements.

- Dressing: Buttons, zippers, and shoes become obstacles when grip strength and dexterity drop.

- Mobility: Walking, climbing stairs, or getting in and out of a car rely on balance and coordinated leg muscles.

- Household chores: Vacuuming, laundry, and cooking involve sustained, repetitive muscle actions.

- Work tasks: Typing, using a mouse, or operating machinery can be compromised, affecting productivity.

Warning Signs You Might Be Experiencing Poor Muscle Control

Not every stumble means a serious issue, but the following patterns often flag a deeper problem:

- Frequent tripping or loss of balance, especially on even ground.

- Difficulty picking up small objects or frequent dropping.

- Uneven or jerky movements when reaching for something.

- Early fatigue during activities that used to feel easy.

- Compensatory habits, like using the stronger side for every task.

If you notice several of these signs persisting for more than a few weeks, it’s time to investigate further.

Strategies to Improve Muscle Control

Good news: many interventions can restore or enhance motor coordination. Below are evidence‑based approaches you can start at home, and those that usually require a professional’s guidance.

Home‑Based Techniques

- Progressive strength training: Using resistance bands or light weights two to three times a week improves muscle fiber recruitment. Aim for 8‑12 repetitions per set, focusing on both major and stabilizing muscles.

- Balance drills: Simple tasks like standing on one foot while brushing teeth, or heel‑to‑toe walking across a hallway, train proprioceptive pathways.

- Coordination games: Toss a ball against a wall and catch it, or practice rhythmic stepping to music. These activities boost timing and neural plasticity.

- Stretching routine: Dynamic stretches before activity and static stretches afterward keep muscle length optimal, reducing compensatory firing.

Professional Interventions

- Physical therapy: Therapists design individualized programs that blend strength, balance, and gait training. They also use modalities like electrical stimulation to prime nerves.

- Occupational therapy: OT focuses on functional tasks - practicing buttoning a shirt, using adaptive utensils, or modifying the home environment for safety.

- Neuromuscular re‑education: Techniques such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) teach the brain to fire muscles in more efficient patterns.

- Medication review: A pharmacist can assess whether a drug is contributing to motor slowness and suggest alternatives.

When to Seek Professional Help

Self‑management works for mild, gradual changes, but certain red flags demand immediate assessment:

- Sudden loss of coordination after a head injury.

- Progressive weakness that interferes with walking.

- Accompanying symptoms like numbness, speech difficulty, or vision changes.

- Any decline that makes you fear falling.

In those cases, schedule an appointment with a primary care physician, who can refer you to a neurologist, physiotherapist, or occupational therapist as needed.

Quick Reference Checklist

- Identify which daily tasks feel hardest.

- Track frequency of stumbling, dropping, or fatigue.

- Start a basic strength‑and‑balance routine (3 sessions/week).

- Evaluate home safety - remove loose rugs, add grab bars.

- Consult a professional if symptoms persist >4 weeks or worsen.

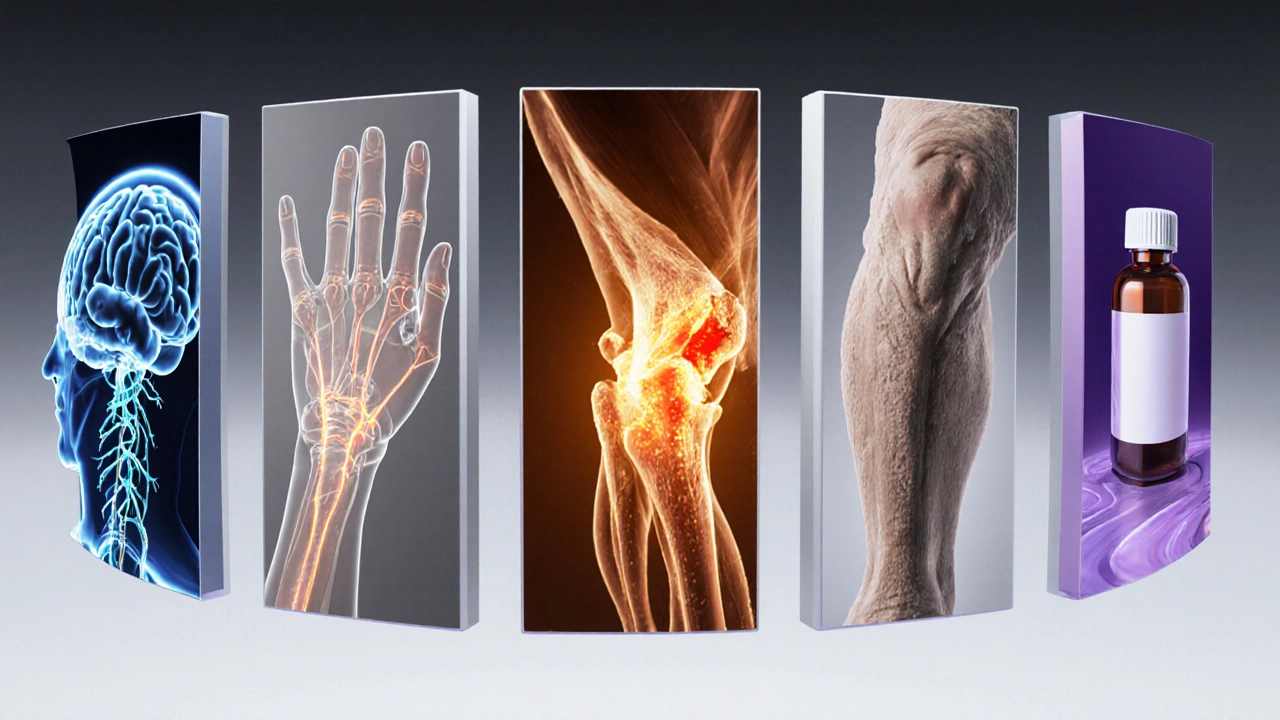

Comparison: Neurological vs Musculoskeletal Causes

| Aspect | Neurological | Musculoskeletal |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Onset | Sudden (stroke) or gradual (Parkinson’s) | Often linked to injury or chronic joint degeneration |

| Primary Symptom | Spasticity, tremor, loss of fine motor precision | Pain‑limited range, compensatory guarding |

| Diagnostic Tools | MRI, EMG, neurologic exam | X‑ray, joint arthroscopy, functional movement screen |

| First‑line Treatment | Neuro‑rehabilitation, medication for tone control | Physical therapy focusing on joint stability, pain management |

| Prognosis | Variable; often improves with intensive rehab | Good if joint health is restored and biomechanics are corrected |

Putting It All Together

Living with poor muscle control can feel like a hidden barrier, but you don’t have to navigate it alone. By recognizing the warning signs, targeting the right exercises, and knowing when to enlist professional help, you can reclaim independence in everyday tasks. Remember, small, consistent steps-like a daily balance drill or a weekly therapy session-add up to big gains over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can poor muscle control be reversed?

In many cases, yes. Neurological conditions often respond well to targeted rehabilitation, while musculoskeletal issues improve with strength, flexibility, and joint‑stabilizing exercises. The key is early intervention and a personalized program.

How long does it take to see improvement?

Results vary. Some people notice better coordination after 4‑6 weeks of consistent therapy, while more complex neurological recoveries may take several months to a year.

Are there any home exercises that help with hand dexterity?

Yes. Simple activities like squeezing a stress ball, rolling a tennis ball between the fingers, or using a pegboard can boost fine motor control. Aim for 5‑10 minutes a day.

Should I avoid certain medications that cause drowsiness?

If a drug’s sedative side effect is affecting your coordination, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Sometimes a dosage tweak or an alternative medication can lessen the impact on muscle control.

What adaptive tools can help with dressing?

Tools like button hooks, zip pulls, and elastic shoelaces reduce the fine‑motor demand of dressing. Occupational therapists can recommend the best combination for your specific challenges.

14 Comments

James Higdon

Oct 6 2025Individuals bear a moral duty to acknowledge their own physical limits. Ignoring the warning signs of poor muscle control is tantamount to self‑neglect. By proactively engaging in targeted exercises, one affirms a commitment to personal well‑being. Society benefits when each person strives for functional independence.

Wanda Smith

Oct 17 2025Consider the hidden agenda behind countless prescriptions. The pharmaceutical conglomerates profit from iatrogenic motor impairment, subtly embedding sedatives that blunt proprioceptive acuity. Meanwhile, regulatory bodies turn a blind eye, perpetuating a cycle of dependency. This covert manipulation erodes our capacity to perform simple tasks that once seemed trivial. One must remain vigilant, questioning every pill offered as a remedy.

Bridget Jonesberg

Oct 27 2025The human body is a symphony of neural impulses and muscular responses, each note calibrated through years of embodied experience. When that calibration falters, the resulting discord resonates not only in the limbs but also in the psyche. A trembling hand reaching for a coffee mug becomes a metaphor for the fragile bridge between intention and execution. Such moments reveal how intimately our sense of self is tied to the reliability of our own movements. In the Western medical narrative, the focus often narrows to isolated pathology, overlooking the existential weight of diminished agency. Yet, interdisciplinary perspectives remind us that motor dysfunction can catalyze a cascade of emotional responses, from embarrassment to anxiety. The embarrassment of dropping a fork in public can seed a lingering self‑consciousness that colors future interactions. Anxiety, in turn, may amplify muscular tension, creating a self‑fulfilling loop of deterioration. Breaking this loop demands more than physiotherapy; it requires a reframing of identity beyond sheer productivity. Patients who learn to view their bodies as collaborators rather than adversaries report a measurable uplift in motivation. Narratives of triumph, such as the athlete who retrains after a stroke, serve as cultural scripts that empower recovery. Conversely, narratives of defeat perpetuate a sense of inevitability that can hasten decline. Therefore, clinicians should incorporate storytelling techniques that highlight resilience. At the same time, caregivers ought to cultivate environments that reduce stigma and encourage experimentation. Only through this holistic dialogue can the abstract notion of ‘muscle control’ be transformed into a lived, hopeful reality.

Marvin Powers

Nov 6 2025Ah, the age‑old excuse of ‘I just can’t’-as if the universe itself conspired to hide the remote. Let’s be honest, a few minutes of balance drills will outshine any lament. Think of it as a tiny rebellion against inertia, peppered with a dash of humor. If you keep mocking the setbacks, progress sneaks up faster than you expect.

Jaime Torres

Nov 17 2025Skip the drama, just start moving.

Wayne Adler

Nov 27 2025I cant believe people ignore simple tips its plain stupid and u wont get any better unless u actually try hard enough.

Shane Hall

Dec 8 2025Imagine the day you can button that shirt without a second thought, the triumph echoing through every routine. Start with five minutes of hand‑strengthening exercises, using a stress ball or a simple rubber band. Pair those drills with mindful breathing to keep the nervous system calm. Track your progress in a journal, noting even the tiniest improvement. Over weeks, those small victories compound into genuine confidence.

Christopher Montenegro

Dec 18 2025The pathophysiology underlying motor dyscoordination implicates deficits in corticospinal excitability coupled with maladaptive proprioceptive feedback loops. Consequently, therapeutic interventions must target both central motor planning and peripheral sensory integration. Empirical studies endorse neuromuscular re‑education protocols that synergize task‑specific overload with transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Adherence to such evidence‑based regimens yields statistically significant enhancements in functional capacity.

Sarah Kherbouche

Dec 28 2025This is what happens when foreign meds take over our health system, they make us weak and lazy. We need to bring back american made treatments and stop this nonsense. Our bodies deserve better than imported junk.

MANAS MISHRA

Jan 8 2026Your observations are spot‑on; recognizing the early signs is the first step toward recovery. I recommend a simple daily routine: five minutes of ankle circles, followed by gentle finger extensions. Combine this with regular posture checks to ensure proper alignment during tasks. Consistency will gradually rebuild the neural pathways responsible for smooth coordination.

Lawrence Bergfeld

Jan 18 2026Start small, stay consistent, and celebrate each micro‑gain; progress is a marathon, not a sprint.

Chelsea Kerr

Jan 29 2026Your determination shines brighter than any limitation 🌟. Keep incorporating those coordination games into your evenings-it’s both fun and effective 😊. Remember, every small step builds a stronger foundation 🏆.

Tom Becker

Feb 8 2026They dont tell u that big tech labs are testing neural chips in plain sight, claiming they are just for 'research'. Those implants mess with your proprioception, making you clumsy on purpose. Wake up, question the headlines, and protect your nervous system before it’s too late.

Laura Sanders

Feb 19 2026Obviously the best approach is a periodized strength program focusing on eccentric loading and neuromuscular priming lack of such protocol leads to stagnation.