Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Causes, Risks, and What You Need to Know

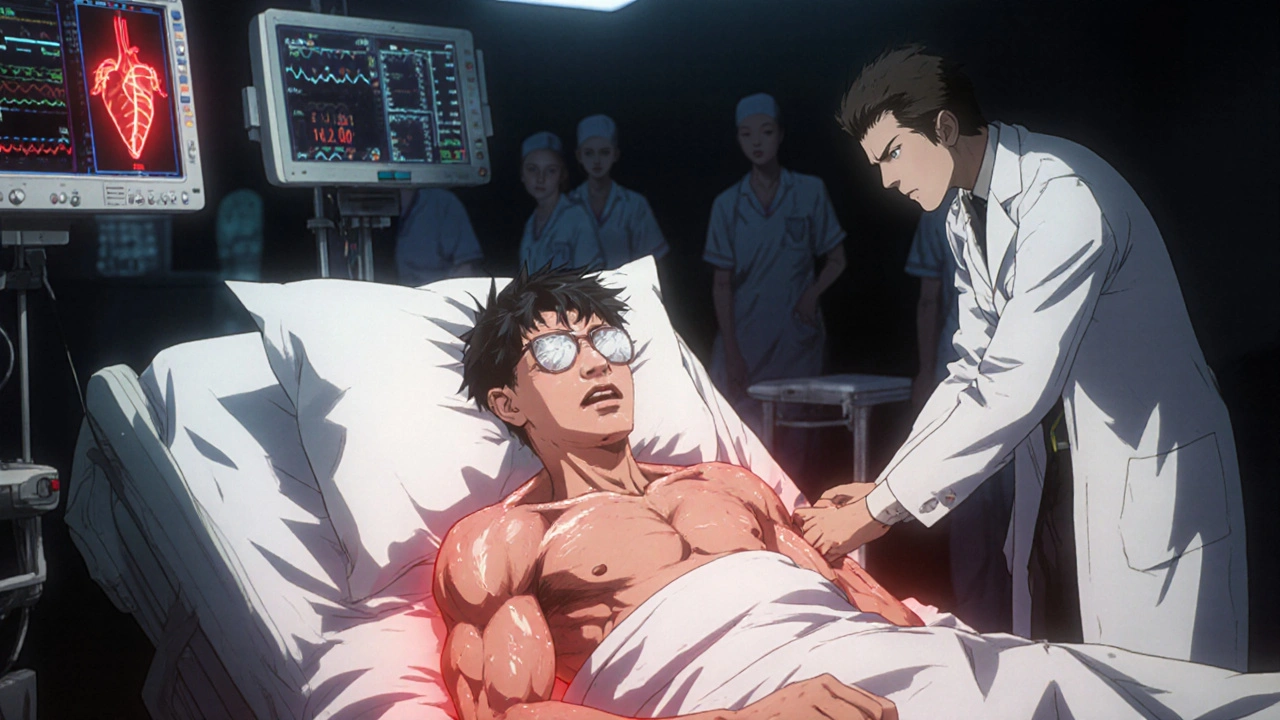

When someone develops neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a rare but deadly reaction to antipsychotic medications that causes high fever, muscle rigidity, and organ failure. Also known as NMS, it’s not just a side effect—it’s a medical emergency that can kill within hours if missed. This isn’t something that happens to everyone on antipsychotics. But when it does, it’s often because the brain’s dopamine system gets slammed too hard, too fast.

Antipsychotics, drugs like risperidone, haloperidol, and olanzapine used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder work by blocking dopamine. That’s how they calm hallucinations and reduce agitation. But if the block is too strong or too sudden—especially after a dose increase, switching meds, or combining drugs—the body can’t adapt. Muscles lock up. Temperature spikes. Kidneys and lungs start failing. It looks like a mix of severe heatstroke and a seizure, but it’s triggered by a drug interaction, not infection or environment.

Dopamine blockade, the core mechanism behind NMS, happens when antipsychotics over-inhibit dopamine receptors in the brain’s basal ganglia and hypothalamus. That’s why symptoms include not just fever and stiff muscles, but also confusion, rapid heartbeat, and unstable blood pressure. It’s not just the brain—every system in the body gets thrown off. And here’s the scary part: NMS can happen even with low doses, especially in older adults or people with dehydration, infection, or existing neurological conditions.

Many people think NMS is rare enough to ignore. But it shows up more often than you’d expect—especially in hospitals or when meds are changed quickly. Emergency rooms see it when someone on a new antipsychotic suddenly can’t move, is sweating like they’ve run a marathon, and won’t respond to questions. If you’re caring for someone on these drugs, watch for muscle stiffness, high fever, or confusion. Don’t wait for all the signs. Early action means survival.

There’s no single test for NMS. Doctors rule out infections, strokes, and other causes. Blood tests show high creatine kinase (a muscle damage marker), elevated white blood cells, and sometimes kidney or liver stress. Treatment stops the drug, cools the body, gives fluids, and sometimes uses dantrolene or bromocriptine to reverse the dopamine block. Recovery can take days to weeks. Some people never fully bounce back.

What you won’t find in most patient guides: NMS can happen even after stopping antipsychotics. It’s not always about starting a new drug—it’s about how your body reacts to changes in dopamine control. That’s why switching from one antipsychotic to another isn’t always safe, even if the new one seems "milder." And if you’re on lithium, antidepressants, or dehydration-prone meds, your risk goes up.

The posts below cover real cases, drug interactions, and warning signs you won’t hear from your pharmacist. You’ll find how risperidone and other antipsychotics tie into NMS, why some people are more vulnerable, and what steps doctors take when things go wrong. This isn’t theoretical. It’s life-or-death knowledge you need if you or someone you care for is on these medications.